Estimated Reading Time: 45 minutes

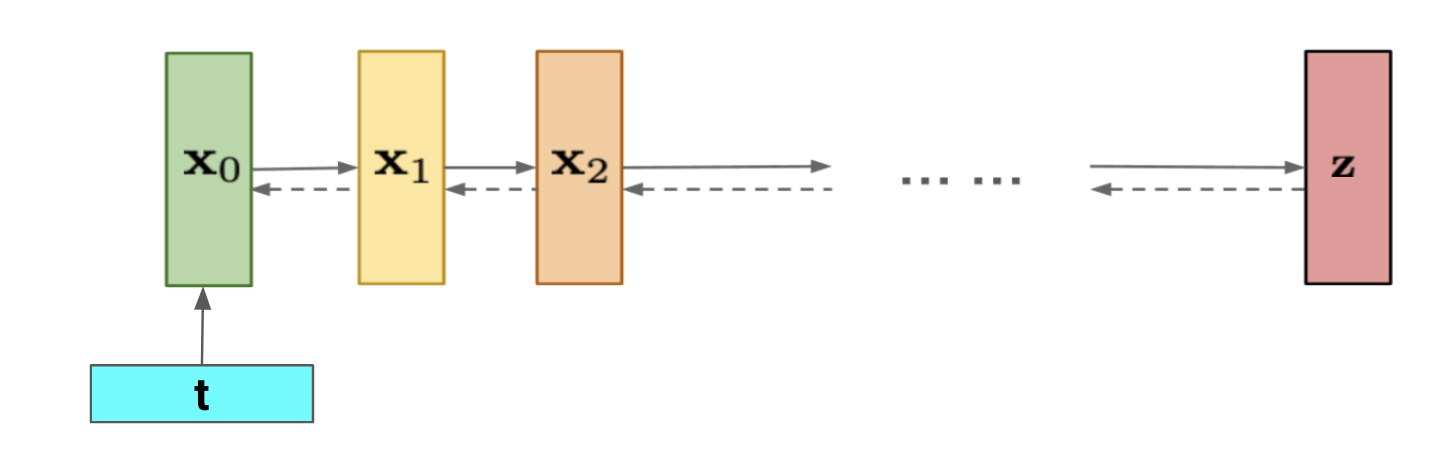

Diffusion models [4,8,9,12] have emerged as a flexible and expressive family of generative models, capable of producing high quality results in multiple domains, including images [3], audio [7], and video [6]. In recent diffusion models, it has also become increasingly common to generate low-temperature samples by conditioning on class labels, either through an external classifier [3] or by training on paired data and periodically discarding the class labels [5]. Of particular interest is the idea of imputation, or conditioning on partial data that has been generated beforehand.

For example, in the context of videos, one can try to generate a 24 frame video conditioning based on a ground truth 16 frames that has already been generated. Such an imputation scheme can then be used to say, extend the video autoregressively by repeatedly applying the imputation scheme through a sliding window conditioning on previous context frames. As another example, one can apply such a scheme on images, generated pixels autoregressively based on images that you have already generated (or generating intermediate pixels for an higher-resolution image based on lower-resolution generated pixels).

Conditional Generation on Context

Multiple different approaches can be taken to do this conditional generation. This includes:

-

Training a classifier-free (conditional) diffusion model [5] directly using previously generated context as conditioning input. This idea is also the basis of a follow up work of [1] (to be released soon).

-

[12] proposes a general method for conditional sampling from a jointly trained unconditional diffusion model (where is the first half and is the second half) by diffusing a noisy data point by replacing the first half of the reconstructed in a DDIM [9] step with the ground truth (generated) . The samples will then have the correct marginals and will conform to the ground truth . This method, however, has shown to be flawed due to the update not including a gradient term that would be required for a correct update: [6] thus propose to approximate the term inside the gradient through a Taylor approximation giving a simple Gaussian: . This leads to the reconstruction guidance objective given by Ho et. al in [6], that updates as where is a weighting factor that tunes the degree of guidance. Intuitively, this L2-loss term "forces" the updates in the replacement method to be more consistent. This approach has been used for videos by combining with predictor-corrector sampling methods (eg. MALA).

Both of the above methods, however, have their own flaws: the first can be shown to not be robust to out of distribution contexts. This can be problematic for domains such as videos, where when extending past baselines, the context will generally be out of distribution.

The second method can also fail due to the approximation of as a single unimodal Gaussian and the fixed size of . Although such an approach can be made better with more complicated approximations [2], or even made asymptotically exact using more sophisticated approximation methods (such as particle filters, see [9]), such methods are generally computationally prohibtive on most practical use cases.

Even with such a course approximation, however, the second approach appears to show some interesting generalization properties which we cover in this blog post, namely a degree of robustness to out of distribution contexts. In this blog post, we give some intuition as to why this phenomenom might occur by proposing that unconditional diffusion models see noisy context as well as clean context during training which leads to this degree of robustness to noise. We justify this finding by comparing it with augmented conditional diffusion sampling, and we show that these two approaches are in fact, functionally equivalent.

Conditioning on Context using an Unconditional Diffusion Sampler

We consider the simple problem of numerical (1 dimensional) trajectory prediction. More specifically, given a time interval (where here we set for simplicity), suppose we have a trajectory, ie. a mapping coordinates defined on the interval . We now wish to find the rest of the trajectory, ie. .

For some cases, this task can be modeled discriminatively, ie. mapping a trajectory defined on the first half of the interval to a trajectory defined on the second half of the interval , ie. . In general, however, for any given trajectory defined on the first half, there can be a multitude of second half trajectories. This leads naturally to a generative approach, generating second half trajectories conditioned on first half trajectories .

Our dataset will consist of full trajectories defined on the whole interval . We define the data distribution of the trajectory fragments defined on the first half (the interval ) as and the fragments on the second half (interval ) as . As described in the first section, we can now model our data distribution using one of two methods:

- Training a conditional diffusion model that directly conditions on the first half (context) of the trajectory, ie. generating directly conditioned on elements of . Given first half trajectories we can then directly generate elements of .

- We can train an unconditional diffusion model to generate the whole trajectory distribution . We can then use imputation as in [6] to conditionally sample the second half trajectory using the reconstruction guidance updates given above. For our simple trajectory examples, we find that simple Langevin sampling methods suffice (so we do not require predictor-corrector strategies as in [6]).

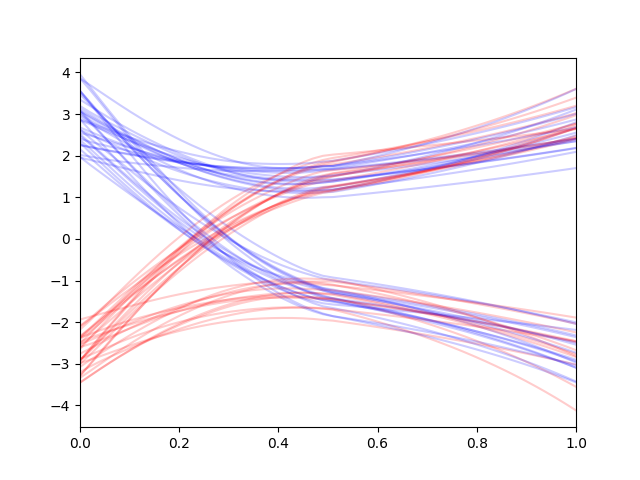

We train these models on a simple stochastic bimodal exponential dataset as shown below:

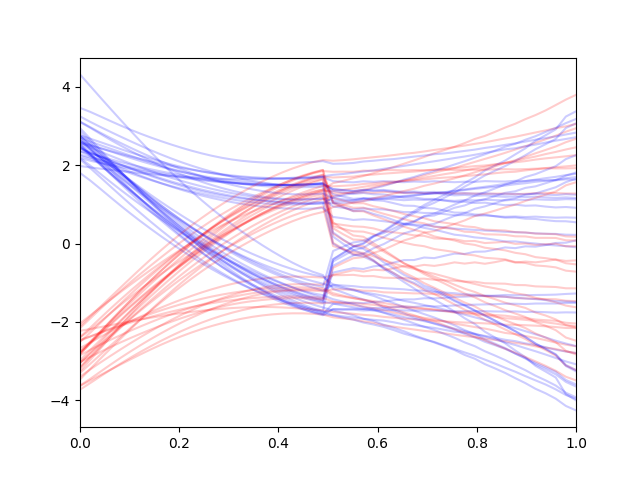

Generating the distribution using the direct conditional diffusion model gives the following generations on clean contexts (when the contexts

are completely in-distribution):

Note that reconstruction guidance gives much more consistent trajectories unlike the replacement method which gives second-half trajectories that make sense on their own but does not make sense in overall context.

Unconditional Diffusion Models Train Context Guidance Models Using Data Augmentation

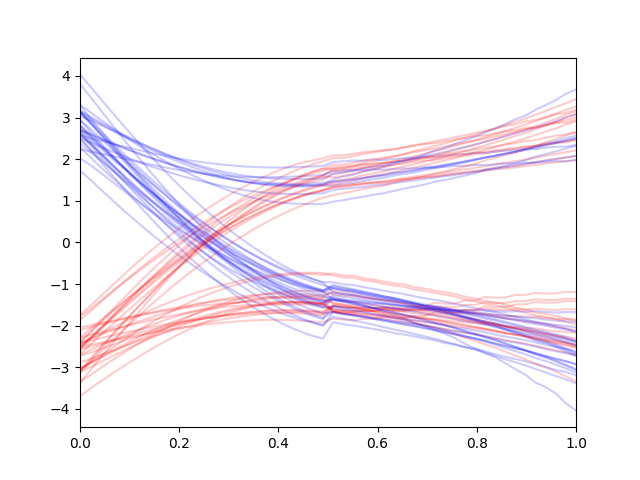

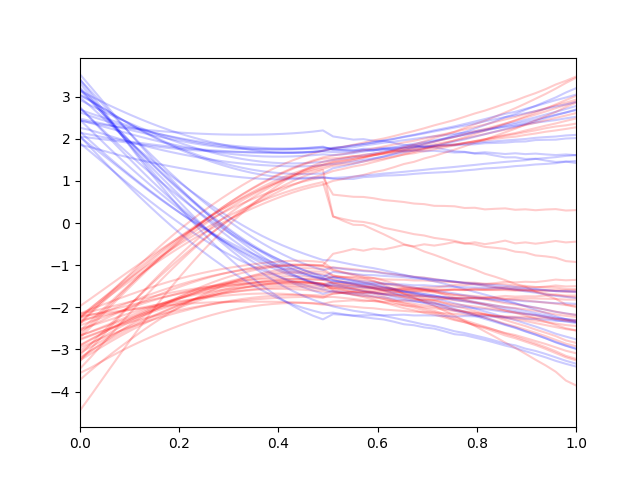

More interesting is what occurs when our contexts are out-of-distribution ie. perturbed in some way. Conditional diffusion models then collapse as they are not trained

to be robust to noisy inputs (as they have never seen noisy conditions during training). Indeed, we see that when we perturb the contexts (we use random bezier and Gaussian perturbations) we get the following generations using the conditional model:

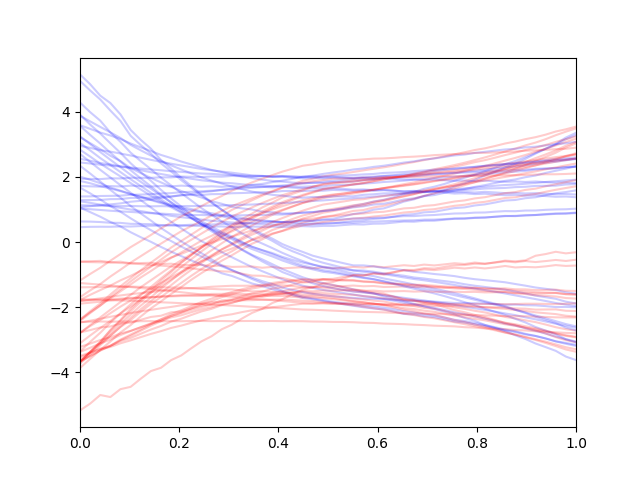

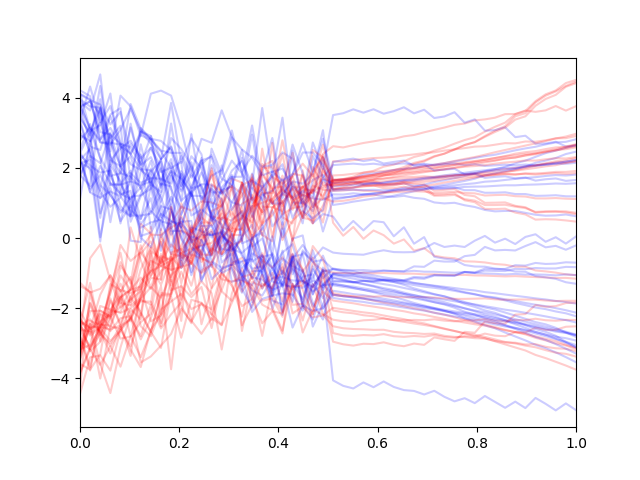

Why are context-conditional generation using diffusion models robust to perturbations in context? We hypothesize that this is due to the training of the unconditional diffusion model. During training, the unconditional diffusion model learns to denoise noisy versions of the first half inputs as well which may be one reason as to why the conditional diffusion model generalizes. These generations then, should in theory be functionally equivalent to conditional generations trained on Gaussian noise augmented contexts (since this is essentially what occurs during unconditional training).

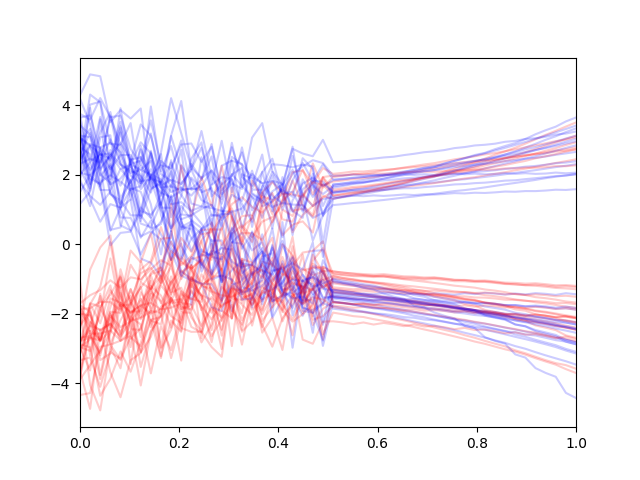

To test this, we train a conditional diffusion model on contexts that are pertubed using some random noise too (along with non-perturbed samples too). This gives us the following conditional generations:

which we find to be roughly equivalent to the unconditional diffusion case!

Concluding Remarks

This blog post demonstrates an interesting property of unconditional diffusion models: namely that they give robust context-conditional sampling when used for inverse problems (such as imputation) with heuristic approximation methods. We hypothesize that this is due to the training methodology of unconditional diffusion models, where noisy versions of the contexts are seen during training. We then provide an intuitive experiment that gives some grounding to this claim.

Some more experiments are obviously neccesary to verify that this phenomenom holds in general, including with 1. Better approximations (other than reconstruction guidance), eg. Diffusion Posterior Sampling (as in [2]) or Twisted Diffusion Samplers [12] for more grounded experiments that rely less on course approximations. 2. Scaling to larger datasets and/or more complicated inverse problems, eg. image inpainting or super-resolution, video generation, and so forth.

This blog post, however, gives an intuitive explanation of the problem and gives some initial experiments that aim to explain this phenomenom.

Citation

Cited as

@article{lee2024unconditional_context_sampling,

title = "Robust Conditional Context Sampling with Unconditional Diffusion

Models",

author = "Lee, Brian",

journal = "www.brianjsl.com",

year = "2024",

month = "Dec",

url = "https://www.brianjsl.com/blog/2024/12/01/unconditional_context

_sampling/"

}

References

[1] Boyuan Chen, Diego Marti Monso, Yilun Du, Max Simchowitz, Russ Tedrake, and Vincent Sitzmann. Diffusion forcing: Next-token prediction meets full-sequence diffusion, 2024.

[2] Hyungjin Chung, Jeongsol Kim, Michael T. Mccann, Marc L. Klasky, Jong Chul Ye. Diffusion Posterior Sampling for General Noisy Inverse Problems, 2024

[3] Prafulla Dhariwal and Alex Nichol. Diffusion models beat gans on image synthesis, 2021.

[4] Jonathan Ho, Ajay Jain, and Pieter Abbeel. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models, 2020.

[5] Jonathan Ho and Tim Salimans. Classifier-free diffusion guidance, 2022.

[6] Jonathan Ho, Tim Salimans, Alexey Gritsenko, William Chan, Mohammad Norouzi, and David J. Fleet. Video diffusion models, 2022.

[7] Zhifeng Kong, Wei Ping, Jiaji Huang, Kexin Zhao, and Bryan Catanzaro. Diffwave: A versatile diffusion model for audio synthesis, 2021.

[8] Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Eric A. Weiss, Niru Maheswaranathan, and Surya Ganguli. Deep unsu- pervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics, 2015.

[9] Jiaming Song, Chenlin Meng, and Stefano Ermon. Denoising diffusion implicit models, 2022.

[10] Tero Karras, Miika Aittala, Timo Aila, and Samuli Laine. Elucidating the Design Space of Diffusion-Based Generative Models, 2022.

[11] Luhuan Wu, Brian L. Trippe, Christian A. Naesseth, David M. Blei, and John P. Cunningham. Practical and Asymptotically Exact Conditional Sampling in Diffusion Models, 2023

[12] Yang Song, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Diederik P. Kingma, Abhishek Kumar, Stefano Ermon, and Ben Poole. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations, 2021.